- Products

- Cell Culture Consumables

- Cell Imaging Consumables

- Bio-Filtration Consumables

- Molecular Testing Consumables

- PCR Tube

- PCR 8-Strip Tube (No Cap)

- PCR 8-Strip Tube (With Cap)

- PCR 12-Strip Tube

- 96 well PCR Plate

- 384 well PCR Plate

- 96 well ELISA Microplate (Undetachable)

- 96 well ELISA Microplate (Detachable)

- 384 well ELISA Microplates (Undetachable)

- 8 well ELISA Microplate Strips

- 12 well ELISA Microplate Strips

- 96 well ELISA Microplate Lid

- 96 well ELISA Microplate Frame

- UV Analyser Plate

- Disposable Plastic Cuvette

- Sealing Films

- Deep Well Plate

- Tip Comb

- Microbiological Consumables

- Pipette Consumables

- 10µl Pipette Tips

- 10µl Extended Pipette Tips

- 20µl Filtered Pipette Tips

- 100µl Filtered Pipette Tips

- 200µl Pipette Tips

- 20µl Graduated Filtered Pipette Tips

- 50µl Graduated Filtered Pipette Tips

- 100µl Graduated Filtered Pipette Tips

- 200μl Graduated Pipette Tips

- 200µl Extended Pipette Tips (59 mm)

- 20µl Filtered Pipette Tips

- 50µl Filtered Pipette Tips

- 100µl Filtered Pipette Tips

- 200µl Extended Pipette Tips (77 mm)

- 200µl Wide-Bore Pipette Tips (Organoid Culture)

- 1000µl Wide-Bore Pipette Tips (Organoid Culture)

- 1000µl Pipette Tips

- 1250µl Pipette Tips

- 5ml Pipette Tips

- 10ml Pipette Tips

- Pipette Tips (Adaptation of Rainin)

- Dispenser Tips (Adaptation of Brand and Dragon Lab)

- Automation Tips (Adaptation of Tecan)

- Black Conductive Tips (Adaptation of Tecan)

- Automation Tips (Adaptation of Hamilton)

- Black Conductive Tips (Adaptation of Hamilton)

- Automation Tips (Adaptation of Agilent)

- Gel Loading Tips

- Serological Pipette (Bagged)

- Serological Pipette (Boxed)

- GMP Serological Pipette

- Serological Pipette (Composite Membrane)

- Serological Pipette (Self Sealing)

- Reagent Reservoir

- Square Storage Bottle

- Pasteur Pipette

- Centrifugal Consumables

- Freezing and Storage Consumables

- Safety and Security Consumables

- Biological Reagents Series

- Prefabricated Products Series

- Cell Culture Plate (Individually Wrapped in Peelable)

- Cell Culture Plate (Individually Paper-Plastic Wrapped)

- Company

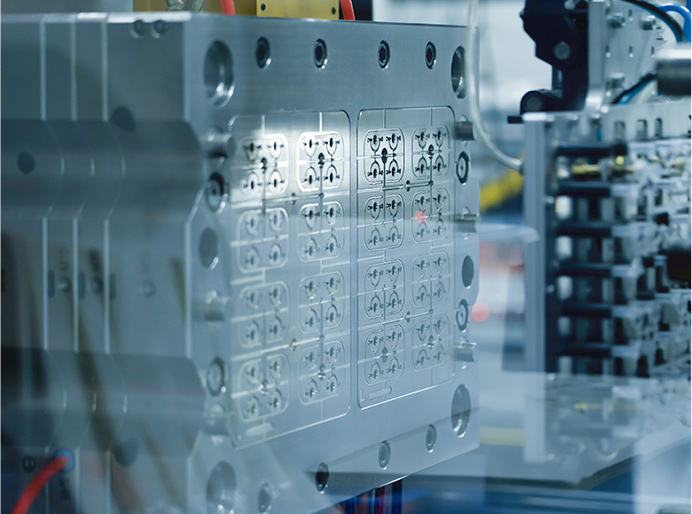

- Customization

- Support

- Press & Events

- Contact

Cell Culture Consumables

Cell Culture Plate

Cell Culture Dish

Cell Culture Flask

Polycarbonate Erlenmeyer Flask

Permeable Insert (PC)

Permeable Insert (PET)

HTS 96 Well Permeable Insert

FACS Tube

Cell Scraper

Cell Lifter

Cell Counter Slide

Cell Culture Tube

Cell Imaging Consumables

Bio-Filtration Consumables

Syringe Filter

Cell Strainer

Bottle Top Vacuum Filter (Vacuum Filter / Storage Bottle)

Bottle Top Vacuum Filter (Storage Bottle)

Bottle Top Vacuum Filter (Vacuum Filter)

Ultrafiltration Centrifugal Tube

Molecular Testing Consumables

PCR Tube

PCR 8-Strip Tube (No Cap)

PCR 8-Strip Tube (With Cap)

PCR 12-Strip Tube

96 well PCR Plate

384 well PCR Plate

96 well ELISA Microplate (Undetachable)

96 well ELISA Microplate (Detachable)

384 well ELISA Microplates (Undetachable)

8 well ELISA Microplate Strips

12 well ELISA Microplate Strips

96 well ELISA Microplate Lid

96 well ELISA Microplate Frame

UV Analyser Plate

Disposable Plastic Cuvette

Sealing Films

Deep Well Plate

Tip Comb

Microbiological Consumables

Pipette Consumables

10µl Pipette Tips

10µl Extended Pipette Tips

20µl Filtered Pipette Tips

100µl Filtered Pipette Tips

200µl Pipette Tips

20µl Graduated Filtered Pipette Tips

50µl Graduated Filtered Pipette Tips

100µl Graduated Filtered Pipette Tips

200μl Graduated Pipette Tips

200µl Extended Pipette Tips (59 mm)

20µl Filtered Pipette Tips

50µl Filtered Pipette Tips

100µl Filtered Pipette Tips

200µl Extended Pipette Tips (77 mm)

200µl Wide-Bore Pipette Tips (Organoid Culture)

1000µl Wide-Bore Pipette Tips (Organoid Culture)

1000µl Pipette Tips

1250µl Pipette Tips

5ml Pipette Tips

10ml Pipette Tips

Pipette Tips (Adaptation of Rainin)

Dispenser Tips (Adaptation of Brand and Dragon Lab)

Automation Tips (Adaptation of Tecan)

Black Conductive Tips (Adaptation of Tecan)

Automation Tips (Adaptation of Hamilton)

Black Conductive Tips (Adaptation of Hamilton)

Automation Tips (Adaptation of Agilent)

Gel Loading Tips

Serological Pipette (Bagged)

Serological Pipette (Boxed)

GMP Serological Pipette

Serological Pipette (Composite Membrane)

Serological Pipette (Self Sealing)

Reagent Reservoir

Square Storage Bottle

Pasteur Pipette

Centrifugal Consumables

Microcentrifuge Tube (No Steriled)

Microcentrifuge Tube (Sterile)

15ml Centrifuge Tube

50ml Centrifuge Tube

Large Volume Centrifuge Bottle

Freezing and Storage Consumables

Screw Cap Tube (Body)

Screw Cap Tube (Cap)

External Thread Cryogenic Vial

Internal Thread Cryogenic Vial

2D Barcoded Tube

Safety and Security Consumables

Biological Reagents Series

Cell Culture Media

Cell Culture Media Supplements

Cell Culture Buffer

Antibiotic

Trypsin

Fetal Bovine Serum

Prefabricated Products Series

中文简体

中文简体 English

English